The Curonian Spit is a sand dune peninsular which separates the Curonian Lagoon from the Baltic Sea. It has been a UNESCO listed site since 2000.

The spit is 98km long and between 0.4 – 4km wide. The northern part is the Lithuanian Curonian Spit National Park, and the southern part is the Russian Kurshskaya National Park, part of the Kaliningrad Oblast.

For me, the Curonian Spit was was a “must visit” destination on our driving trip through the Baltic States. Environmentally, I was impressed with the efforts made to maintain the sand dunes, which tend to move, change and even disappear. Dune stabilisation, protection and management is continual. Forests of pine trees have been planted and maintained. The Curonian Spit is also a place where migratory birds stop off on their travels, so a special place to observe bird life. The tree planting has assisted in conservation efforts, and there was an abundance of wildflowers about.

The car ferry from Klaipedia, on the mainland, took us and our car, on the short trip to Smiltyne on the Curonian Spit – though not without some angst at Klaipedia. We drove round and round and up and down to wharves from which the ferry did not depart. My navigator put in a less than satisfactory performance that day.

We were staying just north of Nida, the main town on the Curonian Spit, a short drive south of Smiltyne. The accommodation was less than memorable, but the sunset that night was splendid.

Just south of Nida, about 1.5km north of the Russian border is the highest drifting sand dune in Europe, the Parnidis Dune, a semi permanent coastal sand dune rising to around 52 metres. Having trudged up and slid down many sand dunes in many places over the years (NZ, Western Australia, Mingsha Dunes in Western China and in the Wadi Rum in Jordan, to name a few) I was very keen to see the Parnidis Dune. There was no question about sliding down this dune. Any such activity would, at the very least be considered as irresponsible human activity. There are designated places where people can walk up the dune, but none for sliding down. Nevertheless, visiting the Parnidis dune was an awesome experience, and really, sliding down 52 metres would have proved pretty challenging.

We accessed various beaches along the Baltic sea coast on pathways through the pine forests. The contrast of the green in the forest to the white sand on the beaches and the dark stormy looking Baltic sea (each time we visited a beach) was quite marked. Apparently, particularly after storms, amber can be found on the beaches. Unfortunately, despite my best endeavours, I did not discover any amber. The wildflowers attracted numerous butterflies, and the walks through the pine forests were quite enchanting.

For centuries, fishing was the main occupation of those who lived on the Curonian Spit. Until the 19th century, most people made their living from fishing. A large number of traditional fishing villages have been buried by sand dunes but Nida, a resort town these days, was a traditional fishing village. The old wooden fishermen’s cottages, painted in red or blue, some decorated with wooden carvings now house museums or provide tourist accommodation. The Fishermen’s Museum occupy one of these buildings. I did not get to visit the museum, as it was not open at any time I was there. Viewing the traditional Curonian fishing boat outside the museum, I hoped it had been confined to fishing in the Curonian lagoon, and did not venture into the Baltic Sea.

I have always been fascinated by weather vanes, from the humble rooster to the very ornate, to the extent that I spend a lot of time photographing wind vanes. I have written about my fascination with weather vanes in the Baltic States and you can see many of the weather vanes I have photographed at Baltic States -Wind Vanes and other photographic themes from other places.

Apparently, unique to Lithuania, carved wooden weather vanes were attached to the main mast of fishing boats – on one version apparently not for the purpose of ascertaining wind direction, but to identify the fishing boat, and the area from which it came. Irrespective of their purpose, I loved the replica weather vanes on poles – replicating the main masts.

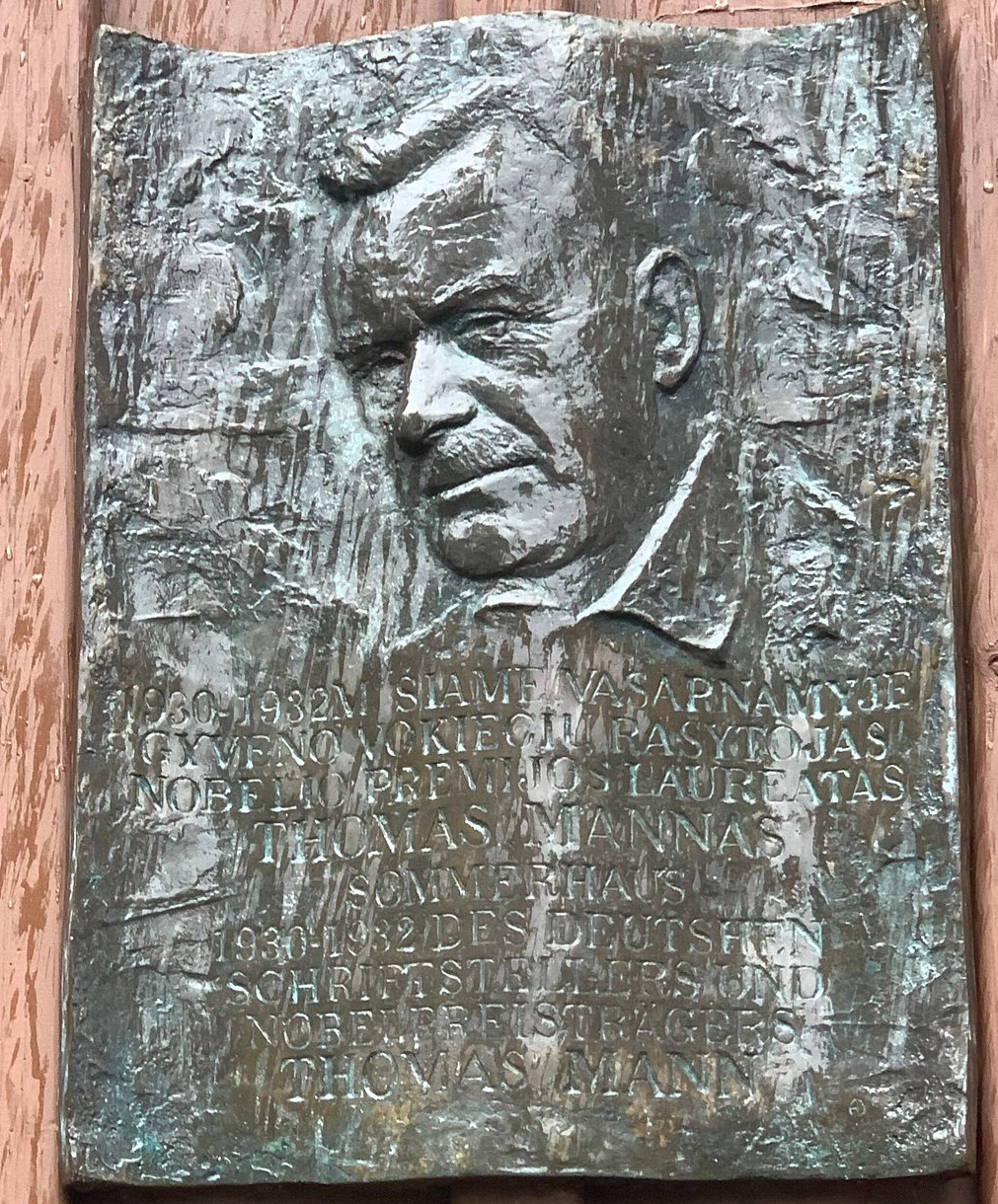

The German Jewish Nobel prize winning writer, Thomas Mann, and his family spent holidays in Nida, and he built a summer house there (1930-32). I had read a lot of his books, and had been intrigued by his relationship with Germany during and after World War II. I was very pleased to visit that summer house, which is now a museum and cultural centre. The house is on a hill above Nida, and has wonderful views. Mann built the house with the money from his Nobel Prize award in 1929.

The museum contains a permanent exhibition about his life, including photographs, books and documents. There was nothing in the museum that appeared to be authentic possessions of Thomas Mann. During the three summers the family spent in Nida, Thomas Mann wrote, among other things, some of his four part novel “Joseph and his Brothers.”

I am very interested in witches, folk stories and myths and legends, but for some reason (ineffective research) I did not discover the Hill of Witches near Juodkrante. It was once the site of a midsummer festival – Jonines – which combined a christian feast with pagan tradition. The site contains a large number of wooden carvings, most depicting characters from Lithuanian folk tales, including devils and witches. I would have loved it.

I try to console myself with the fact that “you can’t see everything”, but I could have seen the Hill of Witches. I did see some wood carvings in Nida, but no witches. Our last afternoon on the Curonian Spit was spent strolling around Nida.

Jurmala

We were heading for Riga in Latvia when we arrived back in Klaipeda. I wanted to visit Jurmala, a resort town on the Baltic Sea, which is about 20km from Riga, primarily to see the beautiful 19th and 20th century wooden houses. These include 23 architectural monuments – of both local and state importance.

I was not disappointed. These houses were a visual delight, and included many styles – art noveau, art deco, neo gothic, neo classic and neo baroque.

Jurmala was a fishing village until the 1830’s, when swimming became popular and the town became a resort town over the years.

We had lunch on Jonas Street, a 1km pedestrianised strip, with numerous cafes to choose from. I enjoyed a baltic herring salad.

The Curonian Spit was a very special place to visit, and the short diversion into Jurmala to view the beautiful wooden architecture was the highlight of the drive to Riga.