We were travelling from Tabriz in North West Iran to Bandar E Astari, on the Caspian Sea, a distance of approximately 398km, visiting Ardabil on the way.

The landscape between Tabriz and Ardabil is varied. Some very arid areas with bare brown hills all around, and occasional greener spots here and there.

Hay was being harvested around the villages we passed through, and every house was crowned with a huge hay stack. The courtyards of many of them were also filled with hay. Dotted along the roadside, crude shelters had been erected, from which people were selling their produce with all manner of produce laid out along the roadside. The further east we travelled the greener the landscape became, and more trees appeared.

In some places we were driving very close to the border with Azerbaijan. Very tall lookout posts, all manned, each one within sight of the next were interspersed between a stretched a barbed wire fence, with very nasty looking razor wire strung along the top. They were so close that I could see the guards and their guns quite clearly. Photographing the guard posts and fence did not seem like a prudent thing to do.

Ardabil is home to the Shrine complex of Safi al-Din (1253 – 1334). He was a mystic and founder of the Safavid order of mystics, and considered to be the founder of the Safavid dynasty. On his death, he was buried in a tomb tower adjacent to his Khanqah, which became a place of pilgrimage.

The shrine complex was built between early 16th century and the late 18th century, and contains a collection of tombs, including that of Shah Ismail I (1487-1524). He became the first Shah of Safavid Iran, ruling from 1501 until his death. The graves of many of those killed in the wars of Shirvan – 1500, and Chaldoran -1514 are also contained in the complex.

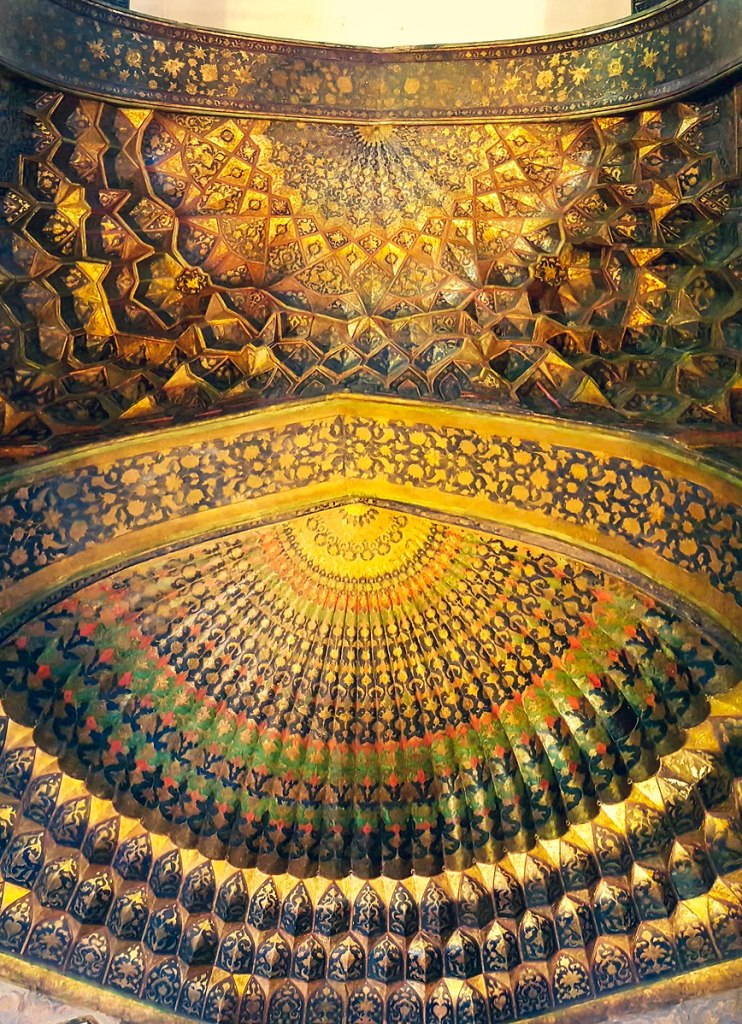

The complex is said to be of the finest examples of Safavid architecture and art. The exterior is decorated with a combination of blue glazed brick and tiles and Kufic and Riqa calligraphy. On the tomb tower of Safi al-Din, the name of Allah is endlessly repeated. There are very fine mosaics, tiling, Safavid calligraphy, Sufi spiritual messages and beautiful Muqarnas. I was quite overwhelmed by the beauty.

On entering the complex, visitors are greeted by a lovely garden. A pathway leads to the Shrine of Safi al-Din which is divided into seven steps, reflecting the seven stages of Sufi mysticism. There are eight gates separating the steps. These gates represent the eight attitudes of Sufism.

The tomb of Safi al-din is approached through the Ghandil Khaneh (the prayer hall), a beautiful hall with gold paint decoration, and magnificent Muqanas. The carved wooden coffin sits under a double shelled dome. The walls are wooden, with lacquer paintings and works of calligraphy as decoration.

Photo Credits Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International Licence

The tomb of Shah Ismail I is contained in a beautiful room, tiled in blue, with inscriptions and gilded murals. The coffin is a carved inlaid wooden case with geometrical patterns. There is a giant hand etched on the blue tiles. The hand shows the Twelver Shi’a sign of Panj-tan-e Al-e Aba (five close relatives of the Phrophet).

Right Photo Credit Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International Licence

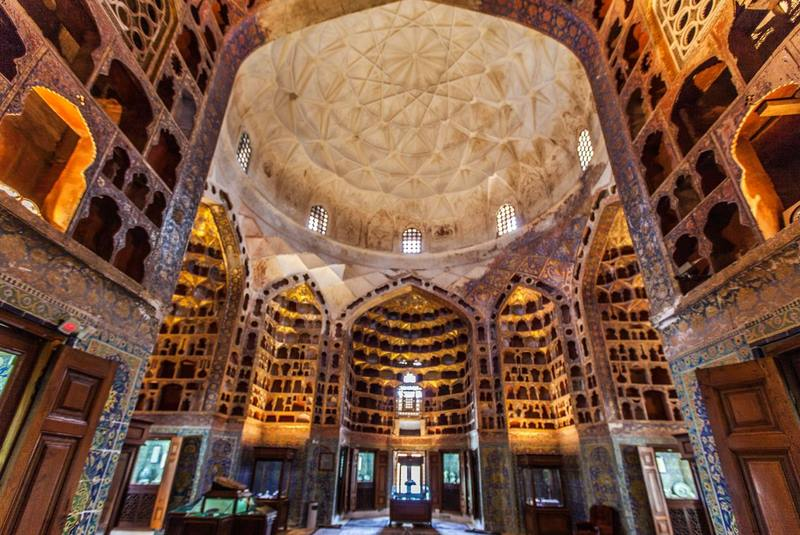

The Chini Khaneh (China room) in the complex contains a collection of Chinese porcelain, donated by Shah Abbas I in 1608. The porcelain pieces were gifts by the Chinese Emperor to Shah Abbas. The initial collection comprised of around 1162 pieces, but after the 1828 invasion by Russia, the Russians took most of the collecton. By 1956 there remained only 805 pieces. The porcelain taken to Russia can be seen in the State Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg.

Shah Abbas apparently ordered that one of the tomb chambers must be converted into a Chini Khaneh, and what a beautiful room it is. The lower walls are covered by colourful tiles up to two metres. Above the tiles, the upper walls contain niches, in the shape of the pieces of porcelain, although the porcelain is now displayed in glass showcases. The muqarnas are spectacular.

A carpet was commissioned for the Shrine in the late 1530’s, which by that time had become a place of pilgrimage. The carpet measures 10.51m x 5.31m, and is the world’s oldest dated carpet. It is able to be dated because of 4 line inscription on one edge, which reads: ” There is no refuge for me anywhere in the world except on your threshhold” then “The work of a slave of the portal Maqsud Kashani” and the date, 946 – Muslim calendar (equivalent to AD1539-1540.)”

The carpet has 25 million knots (340 per square inch) and apparently up to 18 weavers could work on it at any time. The dyes used to colour the carpet were natural and included pomegranate rind and indigo.

The carpet however is not in the Shrine. It was sold to a Manchester carpet firm, who sold it in March 1893 to the Victoria and Albert Museum, London for GBP2,000 in March 1893. William Morris, a British textile designer inspected the carpet for the museum prior to the purchase. He reported it as a”singular perfection – logically and consistently beautiful”. The carpet is displayed in the centre of the Jameel Gallery at the Victoria and Albert Museum, and in order to preserve its colours, it is only lit for ten minutes every half hour. I have viewed this carpet many times, and have darted back and forth every half hour in an attempt to properly examine the detail in the design.

The Ardabil carpet, Photo credit Peter Kelleher, V & A London.

If you would like to read more about the Adabil carpet go to http://vam.ac.uk/articles/the-ardabil-carpet

There is a reproduction of the Ardabil carpet in the Shrine complex.

I could have spent longer at the Shrine complex. There was so much more to explore (eg the Mosque, the school and library), however time did not allow for a longer visit.

After lunch at a Caravanserai (barley soup, a lamb and egg dish and black halva), it was time to drive over the mountains to Bandar-e-Astara. The mountains were misty, but when the mist cleared there were beautiful views of the forest.

We had afternoon tea at the top of the Heyran Pass – eating halva and watching the mist rolling in. The hills were invisible within a few minutes.

That evening, sitting beside the Caspian Sea, I celebrated a perfect day with a glass of non alcoholic Apple Beer.

Images of Safi al-Din. The first image is a miniature of Safi al-Din surrounded by disciples, from a 16th century manuscript of the Safrat as-safa. The second image is a sculpture which is in Safi al-Din Park in Ardabil.

If you have enjoyed this you may also wish to read my previous piece “Off the Beaten Track in Iran https://travelwithgma.wordpress.com/2017/01/22